Sachs & Mearsheimer on ‘Spheres of Security’

Squaring the Security Circle of the Multipolar Century?

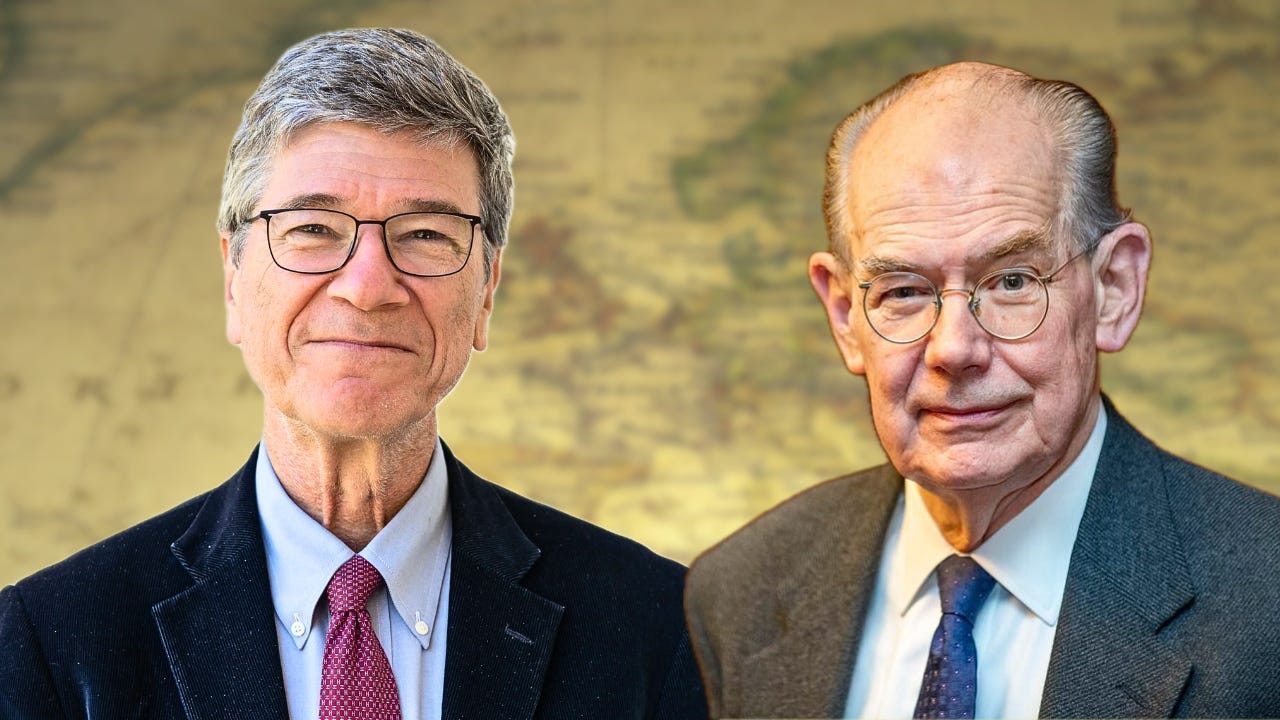

Pascal’s Note: The following is an essay by Dr. Jeffrey Sachs, Professor at Columbia University, in which he proposes to reconceptualize the traditional colonialist notion of “spheres of interest” into what he regards as a prudential concept of “Spheres of Security”. The second part is an email exchange between Sachs and Professor John J. Mearsheimer of the University of Chicago—one of the world’s leading realist scholars in international relations—on the merits and pitfalls of the approach. The essay and exchange are published here for the first time as part of neutrality thinking in IR.

Part 1: Spheres of Security versus Spheres of Influence: A Reconsideration of Great Power Boundaries

Jeffrey Sachs, August 27, 2025

Few concepts in international relations are as contested as “spheres of influence.” From the colonial carve-ups of the nineteenth century to the Cold War division of Europe, great powers have repeatedly claimed the right to intervene in their neighbors’ politics, economics, and security arrangements. Yet this familiar language conflates two very different notions: the legitimate need of major powers to prevent hostile encirclement, and the illegitimate claim of major powers to interfere in the internal affairs of weaker states. The former is better described as a sphere of security, the latter as a sphere of influence.

Recognizing this distinction is more than semantic. It clarifies what should be accepted as legitimate in world politics and what should be resisted. It also helps to re-evaluate historical doctrines such as the Monroe Doctrine and its later reinterpretation in the Roosevelt Corollary, and it sheds light on contemporary debates between Russia and China on the one side and the U.S. on the other regarding national security. Finally, it points toward neutrality as a practical policy for smaller states caught between great powers: neutrality respects the security concerns of their powerful neighbors without submitting to domination or spheres of influence.

Defining the Distinction

A sphere of influence is an assertion of control by a great power over the internal affairs of another country. It implies that the powerful state may dictate or strongly shape the domestic and foreign policies of weaker states within its orbit, thereby subordinating their sovereignty. Influence can be exerted through military force, economic leverage, political interference, or cultural dominance. The underlying logic is hierarchical: strong states are entitled to manage weaker ones.[1]

A sphere of security, by contrast, is a recognition of vulnerability of the great power to the potential meddling of another great power. It refers not to domination but to the legitimate defensive interest of a great power to prevent rival alliances or military forces from establishing bases, covert operations, and weapons systems on its borders. The United States does not need to control Mexico’s government to insist legitimately that Russian or Chinese missiles should not be stationed there. Russia does not need to dictate Ukraine’s domestic politics to be legitimately concerned about NATO infrastructure, CIA operations, and US missile systems from moving into Ukraine. A sphere of security emphasizes external alignments rather than internal meddling.

The crucial difference is this: a sphere of influence undermines the sovereignty of small countries in the neighborhood of great powers, while a sphere of security can be compatible with sovereignty of the smaller countries — and notably if smaller states embrace neutrality.

The Monroe Doctrine as Sphere of Security

The Monroe Doctrine of 1823 is often cited as America’s first great assertion of hemispheric dominance. Yet its original text is more modest than later interpretations. President James Monroe declared that European colonial powers must not attempt further colonization or political interference in the Western Hemisphere, while the United States in turn would not interfere in European affairs.[2]

This was fundamentally a doctrine of reciprocal security. The U.S., still a weak republic on the edge of a continent, sought to insulate itself from the balance-of-power struggles of Europe. Its leaders recognized that European intervention in Latin America would inevitably bring European rivalries into the New World, threatening American independence. Conversely, Monroe promised that the U.S. would not project itself into the Old World’s quarrels.[3]

In this sense, the Monroe Doctrine exemplifies a sphere of security: it protected the Americas from becoming a military staging ground for hostile European empires, while leaving the newly independent Latin American states formally free to pursue their own domestic and foreign policies, without interference either by European powers or the U.S.

The Roosevelt Corollary as Sphere of Influence

Eighty years later, President Theodore Roosevelt’s Roosevelt Corollary (1904) drastically reinterpreted the Monroe Doctrine. Where Monroe had emphasized non-interference, Roosevelt asserted that the U.S. had not only the right but the duty to intervene in Latin American nations that, in Washington’s judgment, failed to meet standards of “civilized” governance or financial responsibility:

Chronic wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation, and in the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power. [4]

This in effect transformed a defensive posture into an imperial one. Under the Roosevelt Corollary, the United States repeatedly occupied customs houses, sent in the Marines, and supervised finances in countries from the Dominican Republic to Nicaragua.[5] Over the course of the 20th and 21st centuries, the doctrine became a warrant for repeated U.S. interventions, regime change, and control—hallmarks of a self-proclaimed and defined U.S. sphere of influence, not a true sphere of security.

The Roosevelt Corollary thus proved repeatedly to be illegitimate in terms of the sovereignty of smaller states in the Western hemisphere: it dramatically eroded Latin American sovereignty in the name of US hemispheric hegemony and the U.S. claim of leading hemispheric stability. The results were less than propitious. The repeated U.S. interventions were dramatically self-serving (e.g. often to defend the narrow interest of well-connected U.S. corporations, such as United Fruit Company in Guatemala and Honduras) and gravely undermined the political development and stability of countries throughout Latin America. Where the Monroe Doctrine had sought to exclude outsiders, the Corollary gave the United States license to act as regional policeman.

Russian and Chinese Concepts of Indivisible Security

The modern vocabulary of indivisible security and collective security, often invoked by Russia and China, resonates well with the idea of a sphere of security. Indivisible security holds that one state cannot enhance its own security at the expense of another’s.[6] For Russia, NATO expansion into Ukraine or Georgia is seen not as benign enlargement but as a direct threat to Russia’s security sphere.[7] For China, U.S. military alliances around its maritime periphery are similarly viewed as encroachments.[8]

US critics claim that Russia and China misuse “indivisible security” as a cover for their attempts at regional domination. US officials and analysts routinely claim that Moscow’s interventions in Ukraine and Georgia, and Beijing’s actions in the South China Sea, are merely attempts to create spheres of influence. Yet these U.S. critiques fail to acknowledge the legitimate security concerns of Russia and China regarding U.S. military placements, including bases and missile systems, and the fact that the US would certainly reject any comparable meddling by Russia or China in the Western hemisphere, as the U.S. vigorously invoked during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.[9] Moreover, the U.S. analysts simply gloss over the oft-stated intention of U.S. security policy to create security chokepoints vis-à-vis these adversaries, for example, in China’s sea lanes.

While the line may sometimes be blurred between true security and mere influence, the concept of indivisible security underscores the distinction. Security interests in buffer zones and next-door neighbors are real. They justify calls on other great powers to stay away, yet they do not justify the regional great power from interfering in the domestic affairs of its neighbors.

Neutrality as the Path to Preserving Security without Influence

How, then, can smaller states in contested regions preserve both their independence and the security of their great-power neighbors? Neutrality offers the most credible and time-tested solution. A neutral Ukraine—sovereign, democratic, but committed not to host NATO or Russian military bases—would respect Russia’s sphere of security while escaping its sphere of influence and would similarly protect the European Union from a westward expansion of Russian military bases and weapons systems. Austria’s declaration of neutrality in 1955 enabled the Soviet Union to withdraw its occupying army from Austria without the fear that its own withdrawal of forces would be followed by an eastward expansion of NATO forces. Historically, Finland’s neutrality served the same function of protecting both the Soviet Union and Finland. [10]

Neutrality is not submission. It is an active diplomatic stance designed to maximize national sovereignty while acknowledging the geopolitical realities of big neighbors. Neutral states can trade widely, maintain independent domestic policies, and participate in international institutions, provided they avoid formal military alignment with hostile powers.

Neutrality can be fragile. Great powers are tempted to erode it, and smaller states may seek protection in alliances, as eventually occurred with both Sweden and Finland, even though neither the Soviet Union, nor the successor state of post-Cold War Russia, ever threatened either country or gave any specific cause of those countries to join NATO. As a normative model, neutrality reconciles two truths: great powers require defensible perimeters, and small states require independence. Only by distinguishing between security and influence can both be honored.

Why the Distinction Matters

Making a clear distinction between spheres of security and spheres of influence has several significant benefits:

1. Clarifies Legitimacy: Security concerns at borders are legitimate; interventions into domestic politics are not. The clear distinction prevents great powers from cloaking imperial ambitions under the guise of defense.

2. Guides Diplomacy: Negotiations over Ukraine, Taiwan, or other flashpoints can be reframed: the focus should be on mutual security guarantees, not domination or regime control.

3. Strengthens International Law: While international law already upholds sovereignty, acknowledging security spheres can be integrated into arms-control treaties, neutrality pacts, and regional security complexes.[11]

4. Promotes Stability: Respecting spheres of security reduces the likelihood of great power war. Rejecting spheres of influence affirms the equal sovereignty of all nations.

Conclusion

International politics has long been plagued by the confusion of security with influence. Great powers may also exploit this ambiguity, justifying interventions as “defensive” while in fact pursuing control. Yet history and theory reveal that these are distinct concepts that can be kept distinct both conceptually and practically.

The Monroe Doctrine in its original form was a doctrine of reciprocal security: Europe should stay out of the affairs of the Americas, and America pledged to stay out of European affairs. The Roosevelt Corollary transmuted the doctrine into one of influence rather than security, subordinating weaker states to U.S. supervision and intervention. Russia and China’s rhetoric of indivisible security reflects their underlying concern for defensible perimeters, especially in an age of missile systems that can reach targets inside Russia and China from neighboring countries and US bases.

The opportunity for diplomacy today is to legitimize the idea of spheres of security while rejecting spheres of influence. Neutrality offers a highly workable and historically tested formula for states potentially caught between great powers. If recognized and respected, this distinction could help to stabilize relations among great powers while protecting the sovereignty of smaller states, thereby creating a more secure international order.

Part 2: John Mearsheimer’s Critique

On Aug 26, 2025, Jeffrey Sachs wrote:

Greetings, John.

I have an IR question.

Do you or others in IR make a distinction between a “sphere of security” and a “sphere of influence”?

I’d like to argue that the great powers are right to assert a "sphere of security” in their respective neighborhoods that other great powers should not trespass — such as no NATO enlargement to Ukraine and no Russian military bases in Mexico — but that this is different from a “sphere of influence” that might imply the “right” of the US to meddle in the internal (non-security) affairs of Mexico or of Russia to meddle in Ukraine’s internal (non-security) affairs. I’m thinking, in essence, of a generalized and reciprocal Monroe Doctrine, but not a Roosevelt Corollary.

Warm regards,

Jeff

On August 27, 2025, John J. Mearsheimer wrote:

Hi Jeff,

As best I can tell, nobody makes that distinction in IR.

I asked Lindsey O’Rourke, who you know and who is writing a book on spheres of influence, and she did not know of anyone who makes the distinction.

A couple points.

I cannot think of any examples of spheres of security in the historical record.

It seems to me that spheres of security would work as a concept only if states could 1) agree on what are their respective spheres of Influence, and 2) credibly commit not to interfere in each other’s spheres of influence.

Then there would be little need for each state to police its own sphere of influence and you would have a sphere of security.

The problem, however, is that the competitive nature of international politics leads states to compete over sphere’s of influence, which incentivises states to manage their own spheres, often in ruthless ways.

It thus seems to me that you have to figure out a way to create a much more cooperative world before spheres of security become feasible.

In essence, you have to take basic realist logic off the table for your idea to work.

I hope that helps and I hope you are well in these otherwise horrible times.

Warmest wishes, John

On Aug 27, 2025, Jeffrey Sachs wrote:

John,

Thanks for the feedback!

My idea (I think) is indeed realist, and along your lines, in the following sense.

Russia and the US meddle in Ukraine, according to realist precepts, for reasons of national security. Yet Ukraine is clearly in Russia’s sphere of security because it is proximate, and hence potentially renders Russia vulnerable to US/NATO missile attacks, subversion, etc. Instead of the current war, the US acknowledges Russia’s valid security interest in Ukraine and reciprocally, Russia recognizes the US legitimate sphere of security in the Caribbean, Mexico, Central America. A truly reciprocal Monroe Doctrine.

Ukraine thereby adopts strategic neutrality and neither Russia nor the US need to declare a sphere of influence — precisely predicated on the fact that neither side will use Ukraine for military-security-covert purposes.

Isn’t that just putting into concepts what you and I say about the blunder of the US trying to expand NATO to Ukraine, or the Soviet Union trying to place military bases in Cuba?

Jeff

On August 27, 2025, John J. Mearsheimer wrote:

Hi Jeff,

I definitely agree with you that the United States — for good realist reasons — should not have tried to bring Ukraine into NATO and should have recognized that Ukraine is in Russia’s sphere of influence.

BTW, I don’t think expanding NATO into Ukraine was done for realist reasons; it was done in pursuit of liberal hegemony.

And I don’t think Russia should meddle in the Western Hemisphere and should recognize it as an American sphere of influence — all for realist reasons.

To build on your rhetoric, this would be a case where both sides recognize each other's Monroe Doctrine.

And it would be a stable world for sure, which would have been the case had we not expanded NATO up to Russia’s border.

I think we are in agreement up to here.

You then talk about a situation where once you have reached mutual Monroe Doctrine’s, there would be no need for either great power to interfere in the politics of its own sphere of influence — what you called a sphere of security, if I understand you correctly.

The problem here is that the world changes and states run the risk that other states that have agreed not to interfere in each other’s sphere of influence will change their mind.

Think about dealing with the United States — especially Trump — in this regard

International politics, after all, is an uncertain world.

This is tied to my point about the difficulty of making credible commitments in international politics.

This situation means that states have to be vigilant, which means they have to manage their spheres carefully to make sure they are not susceptible to outside interference.

That sometime requires interfering in the politics of states in your sphere, which undermines the notion of spheres of security.

All of this also means that a stable world of spheres, which you certainly get in your scenario, is likely to break down over time — maybe a long time.

States have to prepare for that eventuality, which tends to fuel competition — albeit low-level competition for the time being.

Hope that helps.

Your comrade in arms, John

Endnotes

1. Hedley Bull, The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1977), 218–19.

2. James Monroe, “Seventh Annual Message to Congress,” December 2, 1823.

3. George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations since 1776 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 160–63.

4. Theodore Roosevelt, “Annual Message to Congress,” December 6, 1904. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/roosevelt-corollary

5. Walter LaFeber, Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America (New York: W. W. Norton, 1983), 86–110.

6. “Declaration on Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation among States,” UNGA Resolution 2625 (XXV), 1970.

7. Richard Sakwa, Frontline Ukraine: Crisis in the Borderlands (London: I. B. Tauris, 2015), 42–48.

8. Avery Goldstein, Rising to the Challenge: China’s Grand Strategy and International Security (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005), 118–25.

9. Graham Allison and Philip Zelikow, Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis, 2nd ed. (New York: Longman, 1999), 90–95.

10. Raimo Väyrynen, Small States in Big Power Politics (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983), 132–35.

11. Barry Buzan and Ole Wæver, Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 44–47.

Mearsheimer and Sachs are still rehearsing a Cold War duet that mistakes maps for the medium of power. They take it for granted that states are rational actors locked in geographical spheres of influence, forever shadow-boxing in the ontology of anarchy. That was the grammar of the 1990s, but the world has since spoken in another language.

Since 2001, three epochal shocks have shattered the state-centric script: 9/11, driven not by a state but by a network; 2008, triggered not by tanks but by financial derivatives; and the present trade wars, shaped not by armies on borders but by the structural incapacity of states to regulate platforms and supply chains. Trump’s tariffs on India versus China are a case in point: Washington punished New Delhi for Russian oil while sparing Beijing, the supposed peer competitor. That inconsistency is not “realist” but a symptom of structural dependence on Chinese manufacturing and rare earths.

Susan Strange saw this earlier and clearer than either realist or liberal hegemonist. She taught us that the real architecture of power lies not in who holds what territory, but in who sets the rules of production, finance, knowledge, and security. Today that extends to platforms and supply chains — spheres of influence that are not cartographic but systemic. Unlike Mearsheimer’s “offensive realism,” which clings to geography, Strange’s structural power explains why Apple, Amazon, Starlink, and TikTok shape security outcomes more than NATO enlargement ever could.

In 2025, international politics no longer revolves around mutual Monroe Doctrines; it revolves around who controls the code, the cloud, and the choke points of supply. Sachs and Mearsheimer are debating in sepia tones, when the real picture is in high definition: structural power has displaced state geography as the grammar of order. Strange’s framework is not just more explanatory — it is prescriptive. It tells us where to look if we want to understand why the United States can lecture India yet spare China, and why sovereignty itself now depends on system-level resilience rather than border patrols.

What Sachs is trying to do here feels like an attempt to put a finer scalpel to a problem that’s usually treated with a sledgehammer. The “sphere of security” idea does capture something that’s often glossed over: big powers aren’t just meddling for the sake of it, they’re reacting to the fear of being boxed in.

The Monroe Doctrine, at least in its original form, really was about keeping foreign militaries away, not micromanaging Latin American politics. That distinction matters.

But Mearsheimer’s pushback also rings true. In practice, the line between security and influence is almost impossible to police. Once you acknowledge a buffer zone is vital, the temptation to shape that buffer’s politics is overwhelming.

States don’t trust each other enough to simply leave it be. Neutrality sounds great on paper, but it requires both discipline from the smaller state and restraint from the great powers.

If anything, this debate shows the tension between theory and practice. Sachs is sketching the world as it could look if major powers showed self-restraint; Mearsheimer is reminding us how the world usually behaves when fear, mistrust, and ambition take over.

Both are right, but if I had to bet, I’d put my chips on John’s realism over Jeff’s optimism—history suggests it’s the safer wager.