Third-Party Actor Models: Toward a Theory of Neutrality

This is my latest research paper on the theoretical functioning of neutrality in international relations. The paper is currently under journal review and published here as a pre-print.

Introduction

Remarkably little theorization exists in International Relations (IR) on the role of third parties in (armed) conflict. While there is no shortage of case studies of neutral countries,[1] and there exists a large body of scholarship on the historical development[2] of neutrality law and norms,[3] abstraction about the unifying social mechanisms of neutral actors is rare. To be fair, valuable contributions to understanding the general strategic dynamic between third parties and belligerents date back to antiquity, from Thucydides[4] in Greece to Kautilya[5] in India.[6] In recent years, important work has been conducted on the sociological side, how neutrality shapes (and is shaped by) self-perceptions and identity.[7] Some scholars in conflict studies have worked on the role of third parties in conflicts, for instance, Kenneth Cloke’s work on “omni-partiality”[8] and the roles of mediators. Overall, however, we lack theorization about neutral actors in IR. This is problematic not only as a research gap, but it leaves an entire category of actors without the theoretical tools to analyze and comprehensively approach their strategic predicaments. Armed conflict, trade wars, international power struggles, and other violent phenomena are—despite best efforts to eradicate them—still a fact of international life. The question of how third parties should deal with them is, as this paper will show, not only not a trivial one but, in fact, inescapable.

One of the issues preventing theorization is the dispersed nature of the research.[9] Neutrality as a phenomenon tends to be investigated in isolation when it comes to state actors—the traditional locus of most IR neutrality literature—while the neutrality of non-state actors, like humanitarian organizations,[10] sporting organizations,[11] international organizations,[12] or financial institutions,[13] are often not part of the same body of literature. Usually, they are not even conceptualized as being analogous phenomena. Likewise, research on Conflict Studies, Anthropology, and International Law investigates their respective subject matters often separately from the questions of the other fields. Even within history, available literature tends to discuss neutrality-related concepts apart from each other. There is a lot but separate scholarship on notions like Cold War nonalignment,[14] neutralism,[15] or the more recent concept of states seeking “strategic autonomy.”[16] It is often assumed that for an informed discourse, these notions need to be disambiguated and discussed within their own historical and normative contexts. The following attempt at theorizing neutrality challenges this assumption, arguing that a unified neutrality model is possible and helpful in conceptualizing the foundational conflict dynamic that underpins all neutral-belligerent relationships.

To make its case for the value of an analytical understanding and formalization of the term “neutrality,” the paper develops a base model of neutral-belligerent conflict dynamics and derivative models to capture more nuances, for instance, the difference between occasional and permanent neutrality. The paper then establishes why it can be fruitful to think of the term “neutrality” not as a legal, historical, or moral notion, but as an analytical category to capture variations of the underlying social dynamic between third-party actors and conflict parties. Methodologically, the paper uses a reductionist approach, differentiating and discussing the necessary components of conflict systems with third-party actors. It creates graphic representations and formalizations of (a) actors, (b) relationships, and (c) the environment to visualize the discussed dynamics. This includes a thought experiment—a popular methodology in formal philosophy[17]—to establish the central claim that neutral third parties are necessarily part of what the paper calls a “conflict dynamic.” Lastly, the models will be applied to several historical cases, showing their usefulness for analytical purposes. The contestation is that there is an underlying “logic of neutrality”[18] that applies to a variety of actors in international relations (as well as human social contexts more generally) and can be usefully described by the present model. While this discussion is not yet a fully-fledged theory of neutrality, as it does not venture into the necessary hypothesis generation, justification, or selection,[19] it is hoped that the models can serve as an impetus toward that goal.

Regarding its limitations, the proposed theorization of neutrality applies to a diverse range of neutrality domains (a term explained below), but it is constrained to the realm of actively acting parties. The model does not apply to instances when the term “neutral” is used to denote the concept zero (e.g. carbon-neutrality) or a mean number (e.g. pH-neutrality). Neither can it capture the meaning of neutrality when it is ascribed to inanimate objects, territories, or social spaces. For instance, the model does not apply to the notion of “net-neutrality” or “neutrality of the judiciary,” as those describe the idea of communal spaces or platforms that are accessible or applicable at equal conditions to all members of society, while the platforms themselves have no agency on the issue. Equally, the following model does not apply to instances of outside neutralization of uninhabited spaces or inanimate objects, as for instance the neutralization of the waterways or telegraphic cables that occurred sometime in the late nineteenth century. It does apply, however, to neutralized territories inhabited by a population, as those become necessarily actors in their own right.[20]

Neutrality as an Analytical Category

The implicit assumption of the following models is that there is a unifying characteristic among third-party actors that can be usefully described as neutral. We will refer to this as “neutral in the analytical sense,” to describe the position of a third-party actor vis-à-vis two (or more) quarreling counterparts, which creates a triangular relationship that includes peace and warfare at the same time. Stephen Neff once wrote pointedly about this triangularity that “(…) the relationships of war and the relationships of peace are, in practice, constantly interweaving and jostling against one another. War and peace may be opposites. But they are also bedfellows (…).”[21] This interplay is the core of what unites various instances of neutralities across time and space, and analyzing its component parts helps understand the universal predicaments it creates for both the neutrals and conflict parties.

The analytical understanding of neutrality should not be confused with legal or moral notions of neutral actors that assume or imply secondary notions like impartiality, rights, duties, pacifism, passivity, or otherwise socially determined qualifications. The described position is purely relational. Hence, it is ontologically prior to historically or normatively constructed understandings of what a neutral party should be.

In this sense, any actor distancing itself from the primary conflicts of others becomes a neutral party regarding that conflict. Incidentally, this is congruent with a fundamental international law tenet about the applicability of Neutrality Law,[22] as it is the war of two or more external parties that imposes on all parties—belligerents and neutrals alike—the rules of the law of neutrality.[23] It is not the act of the neutral that creates the neutral-belligerent relationship, but the belligerency between the contesting states from which the neutral position arises automatically and without the consent of that party.[24] Why this is the case, not only from the point of view of legal definitions but for logical reasons, too, will be elucidated by the neutrality model in the next section.

Domain-based Differentiation of Neutralities

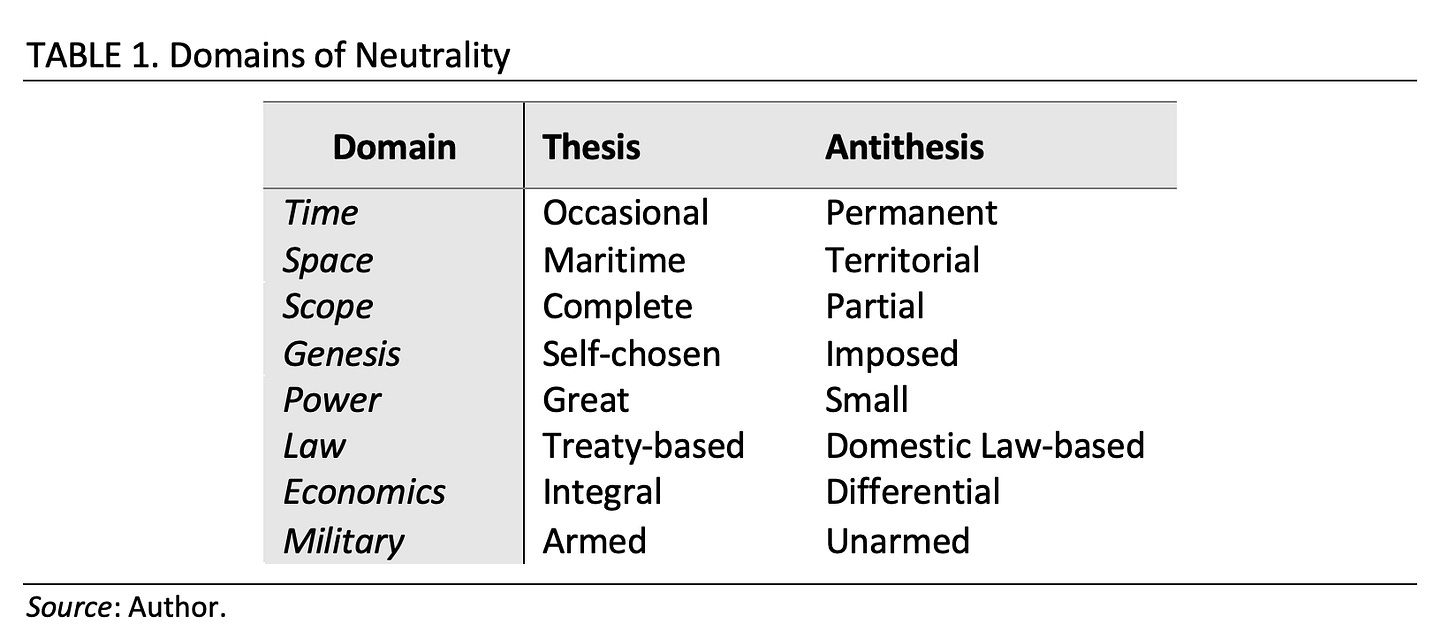

This is not to claim that all neutral actors or instances of neutrality in the international system are the same. Of course, every historical neutrality has its very own case-specific characteristic. Furthermore, depending on where a neutral actor appears and how it behaves, neutralities are often differentiated by the use of various descriptive qualifiers that capture some fundamental aspect of that neutrality. Descriptive qualifiers often cover a specific domain in which neutrality occurs and stand in antithesis to their respective opposites (albeit some domains are spectrums rather than binaries). The most common qualifiers are listed in Table 1.

Since most qualifiers address different domains, they can be mixed to granularly define various neutralities. For instance, Switzerland. As a small power, it has been deploying a treaty-based permanent neutrality for over 200 years, which is (mostly) territorial, armed, complete, and fluctuates between integral and differential treatment of economic affairs, depending on the time period.[25] In contrast, the United States in the nineteenth century is an example of a great power whose self-chosen neutrality was partial (as it was mostly geared toward European conflicts), based on domestic laws, often treated economic and military affairs differentially, and, most fundamentally, was of a maritime nature.[26] Although US and Swiss neutralities are fundamentally different, they are comparable when broken down to the core of what they address, namely the wars of other states.

The Base-Model of Neutrality

Third-party actors in external conflicts—particularly in the Anglo-American traditions—are often assumed to be “standing in the middle” between different power centers or belligerents. This is particularly pronounced in the case of actual warfare, in which neutrals are often explicitly described as “caught in the middle,”[27] or “between”[28] the belligerents. The metaphor extends to popular geopolitical analysis, too, especially under balance of power theory in which “balancing” and “hedging” have become foundational analytical concepts to describe the actions of state actors,[29] often implicitly assuming some form of in-between position of third parties (albeit not always).[30] On an even more fundamental level, the metaphor is linguistically unavoidable when discussing neutral actors in some languages like Chinese and Japanese, as the pictographic characters used to translate “neutrality”—中立 (Zhōnglì in Chinese, or Chūritsu in Japanese)—literally mean “to stand in the middle.” Especially since the terms are the outcome of a cultural norm transmission of an international law concept in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,[31] they stand as a strong reminder of how profoundly the idea of in-betweenness is conceptually attached to the notion of neutrality.

However, in-betweenness is not a useful metaphor to capture the fundamental logic behind third-party (neutral) involvement in conflict situations, especially in the case of armed conflicts. It obfuscates the necessary triangular relationship between the actors as depicted in Figure 1. The international system, much like interpersonal relationships, is inherently bilateral in nature. Every actor maintains separate relationships with all other actors. As long as those are peaceful, normal international relations take place among them, including the exchange of diplomats and the forging of treaties, etc. Even though relationships can change, they change first and foremost on a bilateral level. If two states end up in a war with each other, that does not automatically trigger wars with other states unless alliance or security agreements to this effect have been created beforehand (and are adhered to).

The formal differentiation between elements in Figure 1 and the subsequent neutrality models is as follows.

Circles and pictograms indicate actors

Arrows indicate relationships, either uni- or bi-directional

Symbols qualify relationships

Rectangles indicate the boundaries (or environment) of the system

For the sake of simplicity, we will assume that the situation in Figure 1 depicts a classic interstate war. We will call third-party (A) the “neutral actor,” while calling the conflict parties “belligerents” (B1, B2). The essential part of the conflict dynamic—the one that the mental model of in-betweenness hides—is that each party in such circumstances maintains two relationships with each one of the other parties. (B1) and (B2) find themselves by definition in an “at-war” relationship with each other, while both of them maintain an “at-peace” relationship with (A), resulting in a total of three separate relationships. This triangular situation is the logical prerequisite for any neutrality to occur in the first place. Without a third party (A), there would be no actor to be neutral, and without a war, actor (A) would have nothing to be neutral toward (the next section will deal with the case of peace-time permanent neutrality). There are several important aspects to note about this model and its representation:

First, neutrality in this system is not itself a primary relationship. Only “at-war” and “at-peace” are primary or first-level relationships between the actors of the model, which also creates reciprocity, as both parties have the ability to influence the bilateral relationship. Neutrality, in contrast, occurs as a meta-relational phenomenon—as an attitude of (A) toward the at-war-relationship between (B1) and (B2), arising from the overall constellation.

Second, since the conflict (the at-war-relationship) itself is not an actor but a relationship, no reciprocity takes place in this second-level relationship. That one is determined only by the decisions of neutral actor (A). While conflicts can certainly impact what third parties can or cannot do and affect their decision-making, the conflict itself does not actively or consciously take decisions toward (A); only the belligerents do so. Hence, the neutral attitude of (A) is unidirectional, resembling a vector.

Third, the neutrality of (A) does not modify the at-peace-relationship between (A) and (B1), (B2). While the at-war-relationship does certainly impact the way in which the at-peace-relationships of (A) with (B1) and (B2) take place, the fundamental nature of the relationship remains the same, unless either of the three decides to willfully change it. In this sense, war and peace in the base model are binary states; either one is the case or the other. Albeit there are (of course) different qualitative degrees, both can take.

Fourth, while the neutrality of (A) by definition means that it is not a party to the primary conflict between (B1) and (B2), the neutral party is still engulfed in the overall “conflict constellation,” arising from the triangular interplay. This is an important aspect for two reasons. On the one hand, conceptualizing neutrals as embedded in a larger contextual framework that the primary conflict creates assures that we can factor in secondary effects on the at-peace-relationships arising from the fact that there is tension in the whole system. Usually, both belligerents try to influence the behavior of the neutral toward their enemy, hence neutrals often experience lower-level conflicts with the belligerent parties as they have to fend off—or somehow accommodate—economic, military, or other wartime demands of the belligerents.

On the other hand, using an overall conflict dynamic as a framework also allows us to draw an outer boundary of the conflict system. This matters mostly regarding the conceptual understanding of the prerequisite for a neutral actor to count as such. To explain this, consider the position of the fourth (hypothetical) actor, indicated in Figure 1. Let us call this actor the “man in the moon,” to create the following thought experiment: Suppose that the man in the moon existed as a real being but was located on the far side of the moon, the side never facing Earth, always looking out into the universe. The man in the moon has never heard of Earth, of humans, or of their social interactions. He does not know humans are grouping themselves into nation states, and he does not know that they fight wars with each other. The man in the moon has neither knowledge of nor a relationship with anyone on this planet. If we now suppose that a war breaks out between two countries on earth, the man in the moon, by virtue of lacking all information about them and their at-war-relationship, would have naturally no position on the war, which would make him superficially appear as “neutral” like (A). However, as he lacks a relationship with either belligerent and knowledge about their at-war-relationship, he does not count as a neutral actor in the sense of this model. While this definition might seem arbitrary, it is hard to imagine that a competent speaker of the English language would identify the man in the moon as a “neutral party”, since the aspect of being “a party to the system” is completely lacking. Some form of knowledge about the belligerents and their war seems required for us to meaningfully ascribe “neutrality” to a third party, which the base model takes into account.

This is again congruent with the traditional understanding of neutrality law, for which Oppenheim in his magnum opus on war and neutrality wrote that because “neutrality is an attitude of impartiality deliberately taken up by a State not implicated in a war, neutrality cannot begin before the outbreak of war becomes known. It is only then that third States can make up their minds whether or not they intend to remain neutral.”[32] For the base model as well as for traditional neutrality law, knowledge about the primary conflict of two belligerents is central for there to be the possibility of some form of neutrality arising.

Note, however, that as soon as knowledge about a conflict is established, the model and neutrality law both become inevitable, even if the third party decides that it does not care about the conflict and wants nothing to do with the belligerents. Choosing to reject a positive relationship with belligerents is, in the sense of the model and of the law of neutrality, still a relationship, as it presents a conscious act of position-taking toward the belligerents. Hence, there is a crucial difference between a third-party actor knowing of a conflict but refusing to engage with its belligerents and a completely unaware third party. The latter is not part of the overall conflict constellation, nor would International Law consider it subject to neutrality law. Hence while we could cogently discuss, for instance, the foreign policy of the Maya Empire in Central America during the Anglo-French War of 1213–1214, it would make little to no sense to describe the Maya as “neutral,” since they (most likely) lacked all and any knowledge of that conflict and had no relationship whatsoever with the belligerents. Put differently, the conflict constellation is the applicable realm of neutrality law in Oppenheim’s sense.

Derivative Neutrality Models

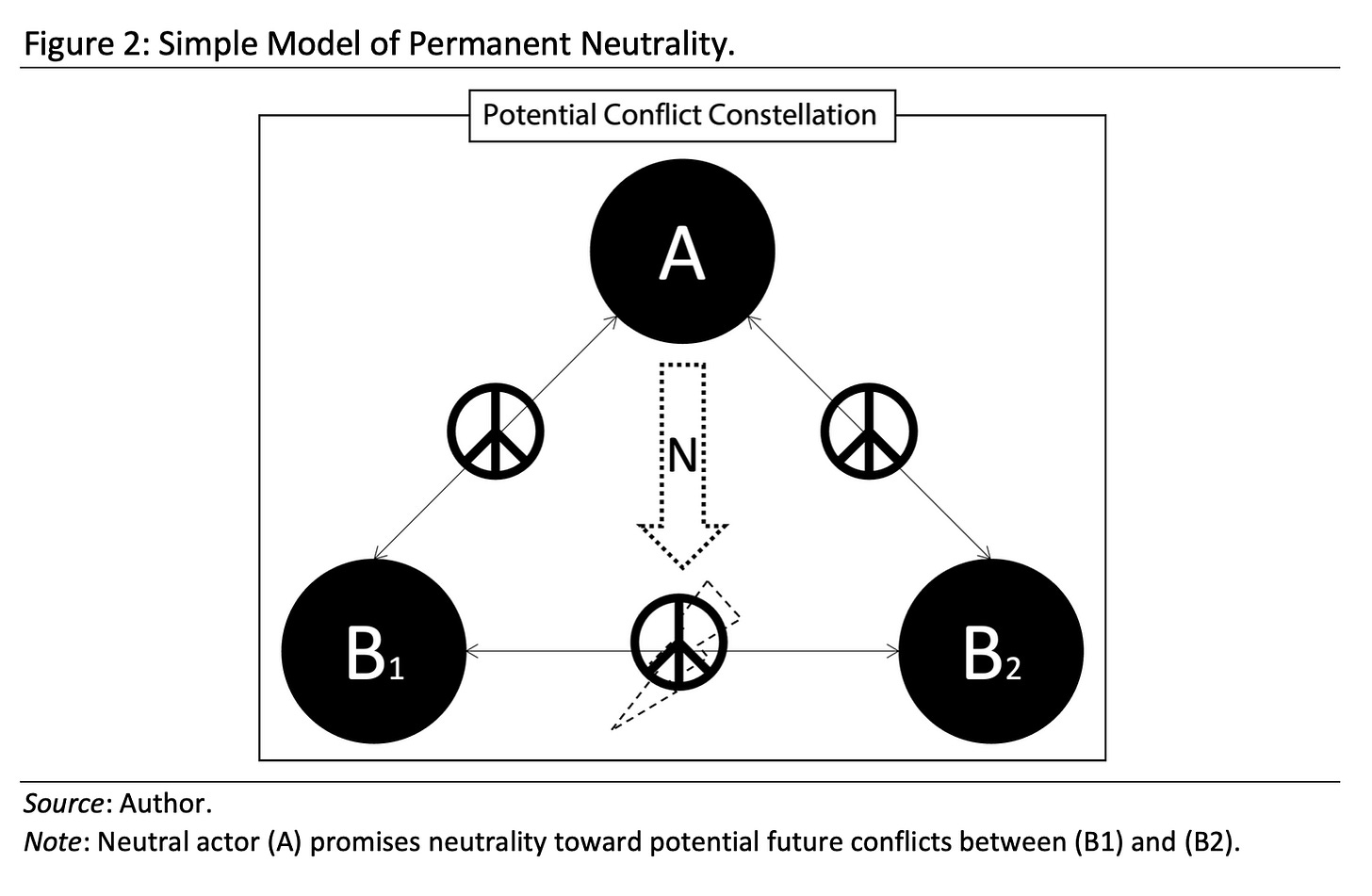

Using the base model as a point of departure, more representations can be built to account for domain-specific neutralities. Most important among them is the difference between occasional and permanent neutralities. Figure 2 shows a slight modification to account for the fact that permanently neutral states have a policy geared not only toward ongoing conflicts but future ones as well. Permanent neutrality, in contrast to occasional neutrality, includes the promise of the third-party actor to observe neutrality in all potential wars, not only actually ongoing conflicts.

In this case, too, the neutrality of (A) is predicated on a conflict, albeit one that does not need to exist yet. The term “permanent” or “perpetual” (as it is called especially in older texts) refers to (A)’s neutrality surviving the confines of the immediate conflict between two belligerents and the applicability of the same policy in the future. The term is, hence, not to be understood as meaning “forever” but merely “lasting.” Although there were older examples of states unilaterally promising permanent neutrality,[33] the first legally codified permanent neutrality was that of Switzerland, established by a multilateral treaty at the 1815 Vienna Congress.[34] Since then, more small powers have adopted permanent neutrality, of which some have disappeared again (like Belgium, Luxembourg, Finland, and Sweden), while others have persisted (e.g. Austria, Costa Rica, Turkmenistan).[35]

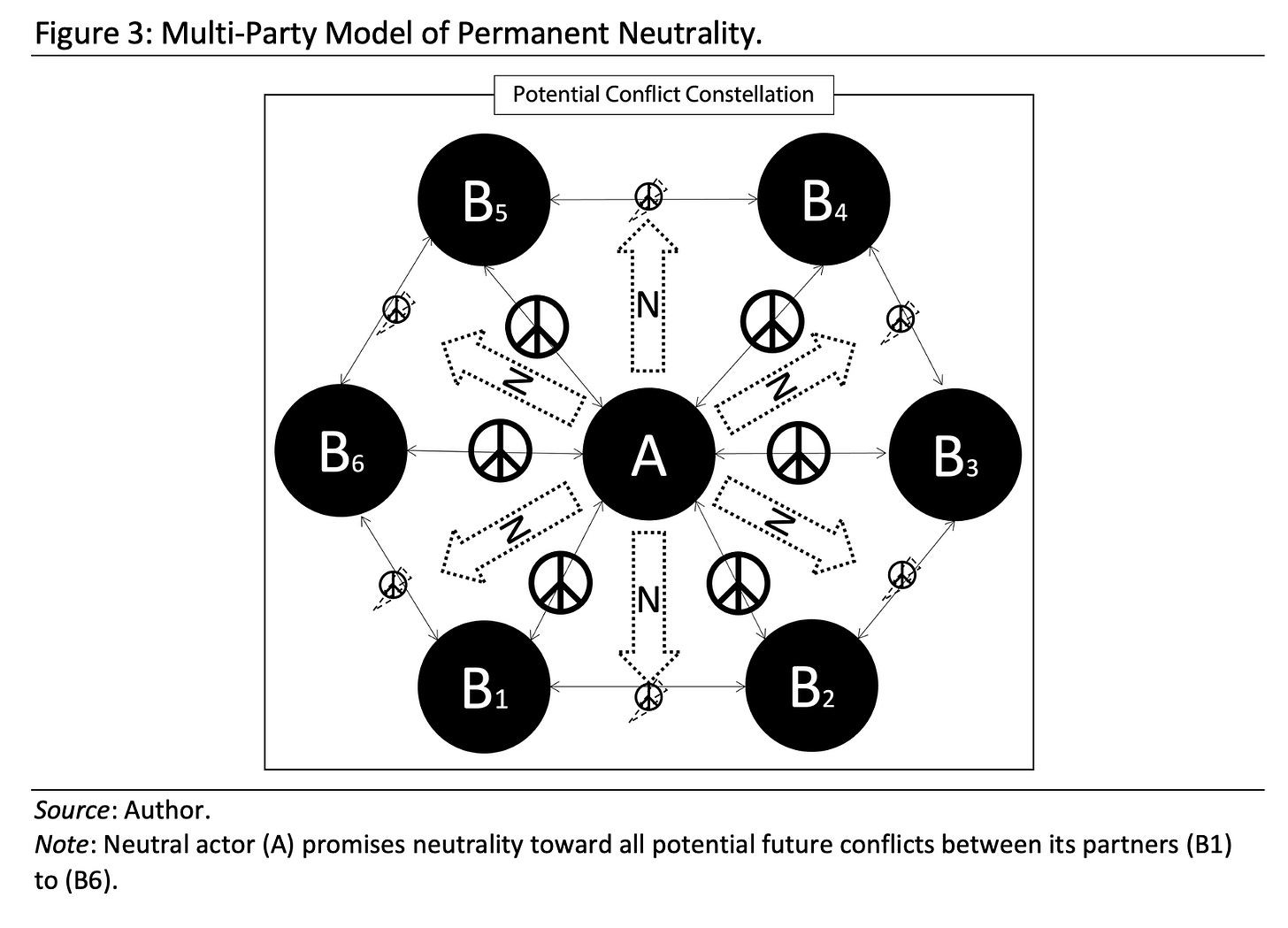

Especially in the context of permanent neutrality, it is worth pointing out that the base model and its derivatives are merely simplifications of actual constellations. In the real world, the number of actors and relationships is naturally much larger and hence more complex. Also, Permanent neutrals must be understood as maintaining the same promise of future non-involvement toward all potential theaters of war. Hence, a more realistic depiction of the permanent neutral’s predicaments puts it in the center from where a multitude of triangular relations emerge, as shown in Figure 3.

Other changes to the base model could be added here to account for more domain-related or case-specific variations of neutrality. For instance, one could use different thicknesses of the bilateral relationship arrows to indicate that (often) neutral actors have a closer relationship with one belligerent than with the other. Or one could add alliance systems to the picture to indicate the collaborations between different belligerent groups during actual conflicts. We could also try to differentiate conflict levels and the neutral's response toward them to understand, in turn, different levels of neutrality. Instead of going through such examples hypothetically, we shall now consider two complex real-world cases of neutrality to illustrate the explanatory power of the model.

Model Applications

Russo-Japanese Neutrality in the Second World War

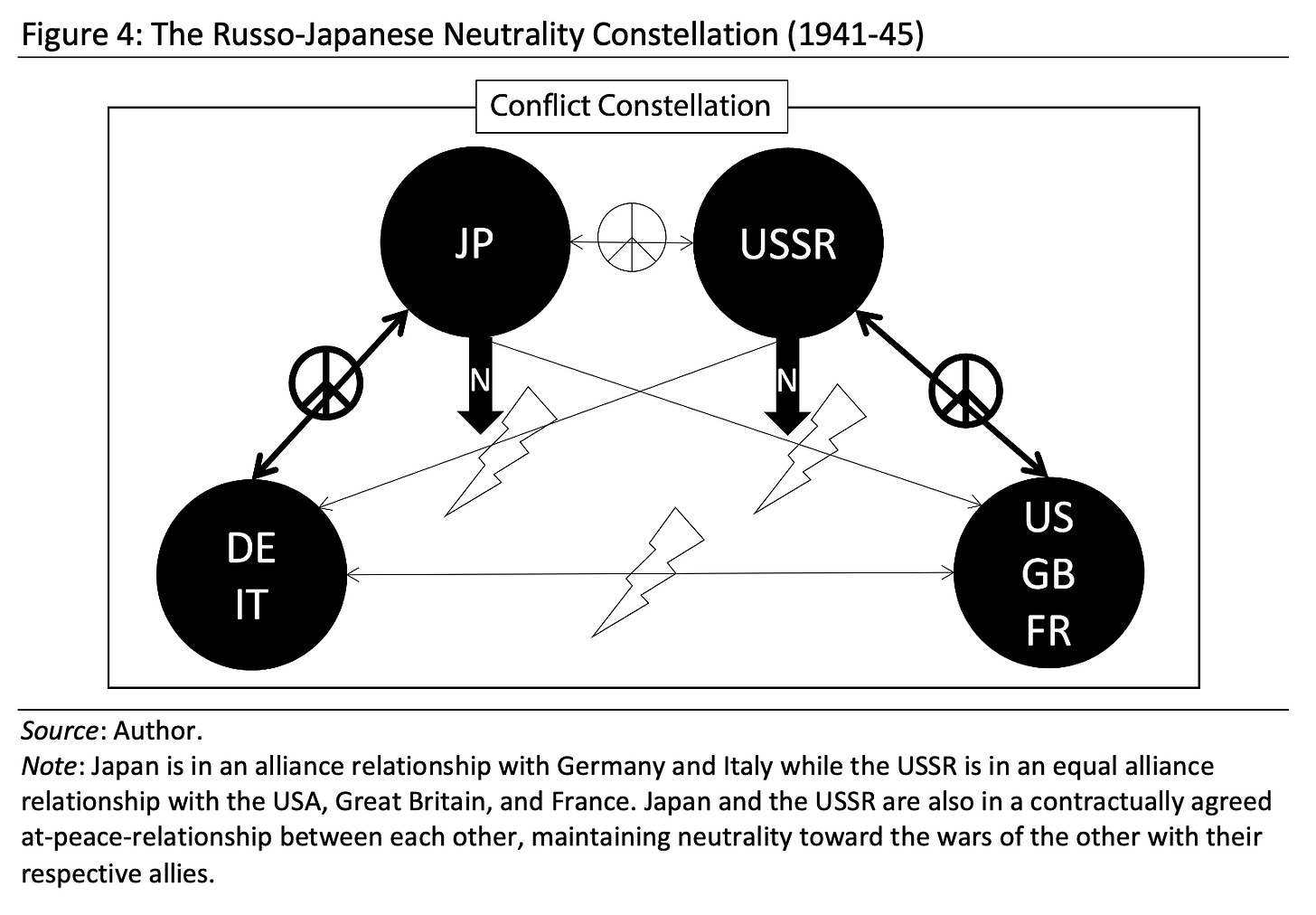

An illuminating case of occasional great power neutrality occurred between April 1941 and August 1945, during which time a “neutrality pact” was in force between Japan and the Soviet Union (USSR). The historical details of the neutrality pact have been meticulously established by Boris Slavisnky,[36] but in a nutshell, the pact was largely the outcome of a temporary alignment of interests between contesters for primacy in East Asia. While their armies had previously even fought bloody battles in the Mongolian plains of Khalkhin Gol in 1939, and Soviet support continued to be crucial to several resistance factions against Japan in the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45), beginning with the Soviet-German Non-Aggression Pact of 1939, a geopolitical case emerged for Moscow and Tokyo to consider a tactical realignment. Especially in Japan, after the initial shock of the Non-Aggression Pact (which Tokyo did not expect) had subsided, a new government decided to seek realignment with the Soviets, the fruit of which was the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact.[37]

This is an often-forgotten instance of World War II neutrality, as both states are usually considered belligerents, not neutrals. Yet, the pact, signed on April 13, 1941, only two months before Germany’s attack on the USSR in Operation Barbarossa, established a contractually-agreed, peaceful relationship between the two Great Powers in North-East Asia by mandating neutrality toward the wars they would be fighting with each other’s allies after Germany attacked the USSR, and later Japan attacked the USA. The relationship was fraught with animosities, suspicions, and proxy warfare in other theaters. However, an overall peaceful interaction—including a trade relationship and functioning embassies—was maintained between them for more than four out of the five years that the pact had specified. Only when the USSR broke the agreement by denouncing it on August 5, 1945, did its provisions seize to govern the relationship, and the USSR declared war on Japan three days later.

While contemporary observers called it “the strangest neutrality that one has ever seen,”[38] and researchers have tried to approach it by applying various IR models,[39] the Russo-Japanese relationship was perfectly understandable as a bilateral win-win agreement for its two parties, and it can be represented through a neutrality model, as shown in Figure 4, which depicts the Second World War situation after Japan’s attack on the USA in December 1941.

Note that this representation lumps together allies on both sides and, for simplicity's sake, ignores a few co-belligerents like China, Finland, or Romania. In this simplified model, Germany and Italy form one set of allies with which Japan is in a supportive at-peace-relationship, while Great Britain, France, and the USA form the other set with a supportive at-peace-relationship. The two alliances are in an at-war-relationship with each other, while, simultaneously, Japan finds itself in an at-war-relationship with the USA, Great Britain, and France, and the USSR is equally in an at-war-relationship with Germany and Italy. Among themselves, Japan and the USSR remain in an at-peace-relationship that gives rise to each one’s neutrality toward the other's at-war-relationship with their respective allies.

Despite the simplification, by disambiguating the most important bilateral relationships, it becomes clear that both neutralities (that of the USSR and Japan) are directed toward very specific parts of the Second World War Conflict Constellation. Hence, belligerent neutrality is not a contradiction in terms, but it can be part of a multilateral conflict constellation. While international actors cannot be simultaneously at war and at peace in one and the same relationship, if we differentiate the various bilateral relationships, we see that they can maintain peace with one party while being at war with another, and in the process remain a neutral third party toward an external conflict.

While this might seem confusing, since Japan, Germany, and Italy are often thought of as part of the same alliance, just like the USSR, Britain, France, and the USA, the actual conflict constellation was much more complex than a simple two-club rivalry. This has to do with the nature of the bilateral support agreements that were struck during this period, of which the Soviet-Japanese neutrality pact was only one. This aspect touches intricately on the issue of third-party actors and merits a short explanation.

Bilateral Support Agreements

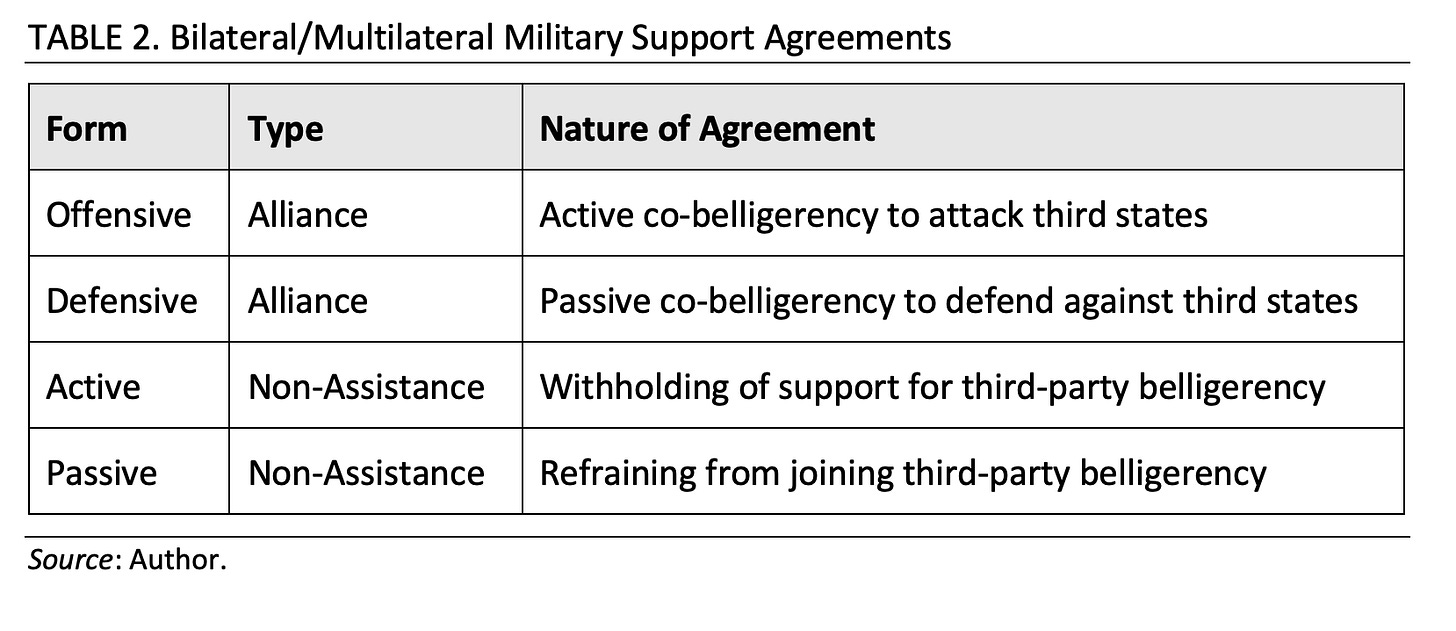

There are at least four different types of bilateral support agreements, expressing different levels of joint conflict approaches toward third parties that states can engage in. Those represent what some call “commitment levels,” and they can be expressed in various taxonomies.[40] They are idea types, which vary in their scope but, in general, one can distinguish between the following four.

First, there are offensive alliances that are conducted for the sake of active joint war-making against a third state. The Triple Alliance by Uruguay, Brazil, and Argentina against Paraguay in 1865 is an example thereof,[41] or, in a weaker version, also the secret additional protocol to the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact of 1939, in which both parties agreed to partition Poland.[42] The US and British-led “Coalition of the Willing” in 2003 to attack Iraq can also be counted to this category of offensive alliance agreements, albeit in a less formalized manner.[43]

Secondly, there are defensive alliances in which contracting parties agree to come to each other’s help should one party be attacked by a third party. The Covenant of the League of Nations[44] or the Charter of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)[45] are examples (although the latter’s Article Five does, in fact, not establish an automatic military assistance relationship in case of attack, but it is widely assumed that such would be the practical outcome in case of an attack on a member).

Third, there are active non-assistance agreements states can make, in which they promise their counterparts not to aid any third party that might end up in a war with the counterparty. The official part of the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact (Article 2) would be the main example here, in which both sides promised not only to maintain peace amongst themselves but not to undertake action that would aid the warfare of a third state against the other one.[46]

Lastly, there are passive non-assistance agreements in which the contracting parties agree not to join the warfare of third states against the other party but might reserve the right (explicitly or implicitly) to support such third-party war efforts. The Soviet-Japanese neutrality pact is the example here, as Stalin explicitly refused to grant Japan a German-style Nonaggression Pact, since he wanted to continue supporting the Chinese resistance effort against Japan, albeit with reservations.[47] He was, however, willing to promise not to join that war as an active belligerent. Table 2 is a summary of the four bilateral support agreement types.

Due to the nature of these agreements, the varying levels of sincerity with which they were undertaken, and the fluid developments of the various theaters of war, the conflict constellation of the Second World War was a most complex web of arrangements, leading even to belligerent neutrality, as shown above.

The Russo-Ukrainian War

So far, we applied the triangular third-party relationship model to a conflict constellation disambiguated based on individual war/peace relationships. Another way of using this type of analysis is to understand the different qualitative levels of multi-actor conflict dynamics. Instead of disambiguating the number of bilateral relationships, we can disambiguate the different spheres in which conflict takes place and analyze the attitude of third-party actors toward them. A good example is the Russo-Ukrainian Conflict/War with its different phases and conflict levels.

As of the time of writing, the warfare between Russia and Ukraine is still ongoing and the debates about its causes and narratives are strongly contested. We shall not try to venture into the specifics of the conflict (nor discuss the situation of Crimea) but take its existence as a given fact and define its beginning as the year 2014 when for the first time mass violence broke out on the territory of Ukraine,[48] and military action led to what International Law refers to as a Non-International Armed Conflict (NIAC) that later transformed into an International Armed Conflict (IAC)[49]—albeit even this differentiation of the two stages is a contested notion.[50]

On a first (local) level, the Russo-Ukrainian War contains a conflict between Ukraine’s central government and opposition forces in the two eastern oblasts of Lugansk and Donetsk. Especially between 2014 and 2022, before the large-scale intervention of Russia in what it calls a Special Military Operation. The NIAC Constellation included a large number of actors. On the one hand, the Ukrainian Government received significant diplomatic support from Western states, especially Germany and France, while also receiving military training and aid from other NATO states, especially the USA and the UK.[51] On the other hand, Russia provided extensive diplomatic and military support to the two breakaway oblasts. The most neutral position in this constellation was taken by Belarus,[52] which in the first years of the conflict managed to maintain a working relationship with all parties and consequently even function as the host of the “Minsk Agreements” (named after the Belorussian capital) that were negotiated in 2014 and 2015, to bring the conflict to a political settlement. Hence, we can position Belarus as the pivotal neutral state ‘in the analytical sense’ in the center of the model to investigate its relationships and neutral attitudes toward the two different levels in which the conflict was playing out.

Figure 5 shows, in the lower part, the military level at which a hot shooting war raged between the Ukrainian national forces and the breakaway oblasts. On the upper part, we see the structural level at which the supporting sides—Russia supporting the oblasts and NATO countries supporting Ukraine—ended up in a second conflict, fought out not with weapons but politically and economically in the United Nations and through economic sanctions. Belarus maintained a neutral position toward both conflicts, resulting in a functioning working relationship with all parties.

While Belarus used to have a neutrality clause in its constitution going back to the time of the dissolution of the USSR[53]—even while being a Union State member with Russia—the concrete neutrality of this case was based mostly on the necessities of the conflict constellation.[54] However, as the conflict progressed and the institutional integration of military support on both sides deepened, Belarus also got absorbed into the larger structural and military conflicts. In 2022, not only had the neutrality clause vanished from its constitution, but part of Russia’s incursion into Ukraine happened from Belarusian territory. Hence, for developments since the beginning of large-scale warfare between Russia and Ukraine, it makes sense to focus on other states that maintained an analytically neutral position toward the conflict in one way or the other. Equally, the two ‘People’s Republics’ in the Donbas disappeared at this stage of the warfare, as Russia incorporated them (and two more Ukrainian oblasts) into its state territory. Whether one accepts those claims or not, for the power dynamic on the ground, Donetsk and Lugansk seized playing a political role, being superseded by Russia as the overall actor in charge of both—the hot shooting war and the structural conflict with NATO.

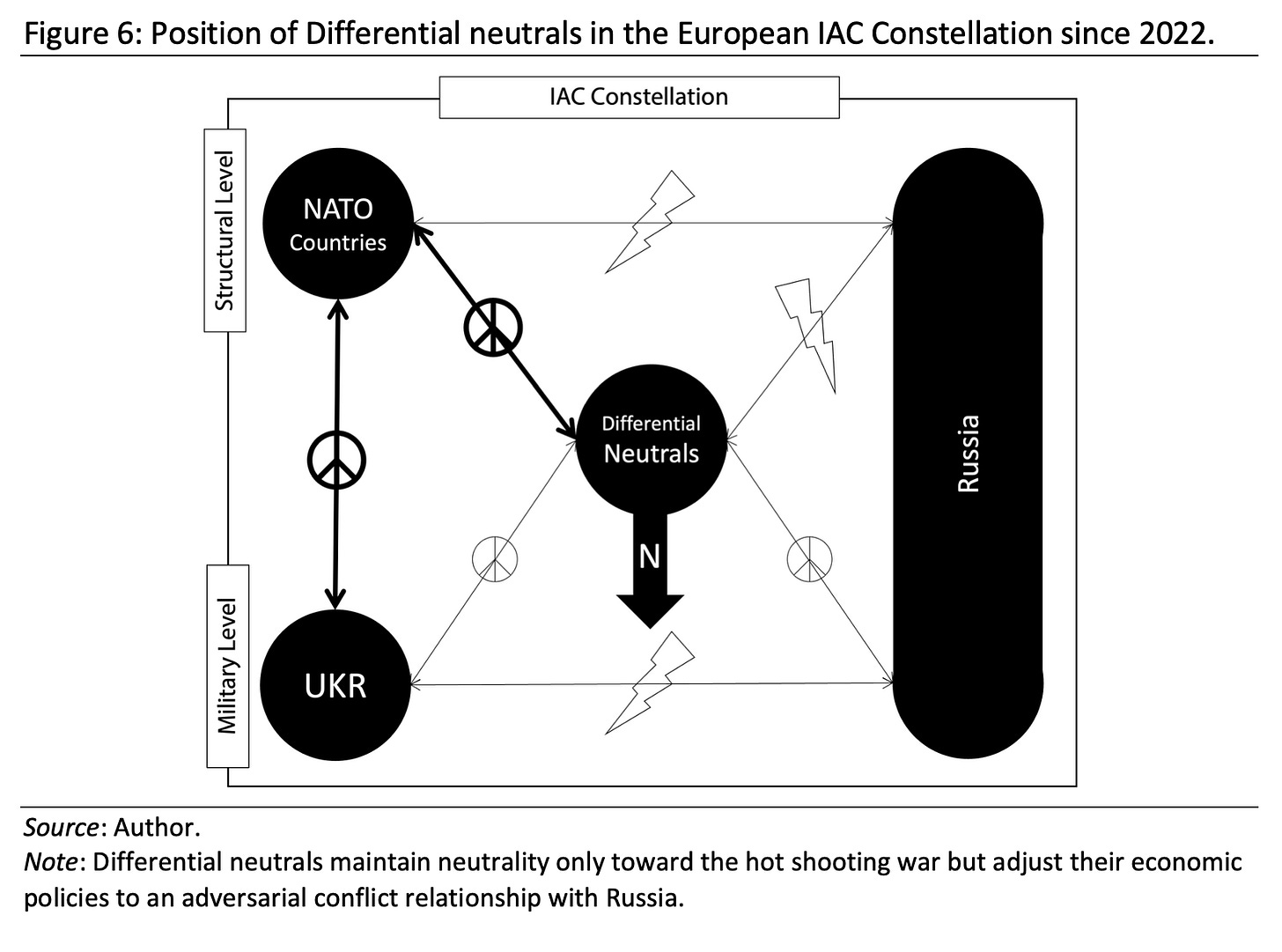

First, we can look at a category of countries that maintained military neutrality only—meaning that while they did not send weapons or other “lethal aid” to either side of the hot shooting war, they did, in fact, impose economic sanctions on the Russian side. Switzerland, Austria, and Ireland are examples of officially neutral states with neutrality clauses either in their constitutions or legal codes that belong to this category. Other states without neutrality policies could be added to this list, like Japan or South Korea. In the analytical sense of this paper, they implemented a differential neutrality toward the two conflict levels, shown in Figure 6.

A hallmark of differential neutrality is that states direct their neutral attitude only toward the hot-shooting war between the primary belligerents. When it comes to the structural conflict on the economic (and ideological) level, they adopt antagonistic policies toward one side of the conflict, which, invariably, leads to similar countermeasures by that side, including sanctions, the revocation of civilian overflight rights, travel restrictions, and other sovereign measures intended to put political pressure on the adversary.

On the structural level, the differential neutrals (neutral only militarily) closely coordinated their political actions with NATO and EU states, which does not amount to a formal alliance but, nevertheless, represents a very strong favoring of one side over the other. For the case of Switzerland, this led to the point at which, in the summer of 2022, Russia rejected the country’s bid to function as protecting power for Ukraine in Russia (a common diplomatic practice for neutrals), arguing that Russia regarded Switzerland as an “unfriendly” state—having it included previously on such a list[55]— not a neutral party to the conflict.[56] Switzerland, since the early days of the conflict, emphasized that it kept to the rules of military neutrality.[57] However, Russia was not referring to this level of the conflict in its accusation, as Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov explained on two occasions in early 2024:

I spoke with Swiss Foreign Minister Ignazio Cassis […] I explained to him why we could no longer view Geneva as a truly neutral platform that could facilitate meetings on settling differences. Bern has taken an overtly anti-Russia position. It is enough to say that they recently approved a foreign policy concept saying that Switzerland is striving to enhance European security not with Russia but against it. This is written in their official documents. What kind of mediation can they provide? Now they are trying to impose on others their mediation on Ukraine but nothing will come of it. This player cannot be trusted.[58]

Lavrov repeated this point two months later when Switzerland proposed to hold a peace conference:

Switzerland is not fit enough as a venue for peace talks. Formerly it was a neutral country. Its territory as that of the other neutral countries (Austria, Finland, Sweden) hosted various conferences, because its platform was comfortable for everybody. Currently, Bern has unequivocally sided with Ukraine. And it is not just supports [sic] all Western sanctions, but in some issues even acts as the leader.[59]

To the Russians, it was not primarily the attitude in the hot shooting war that determined their perception of other countries’ neutralities—it was the behavior toward the structural conflict that they assessed.

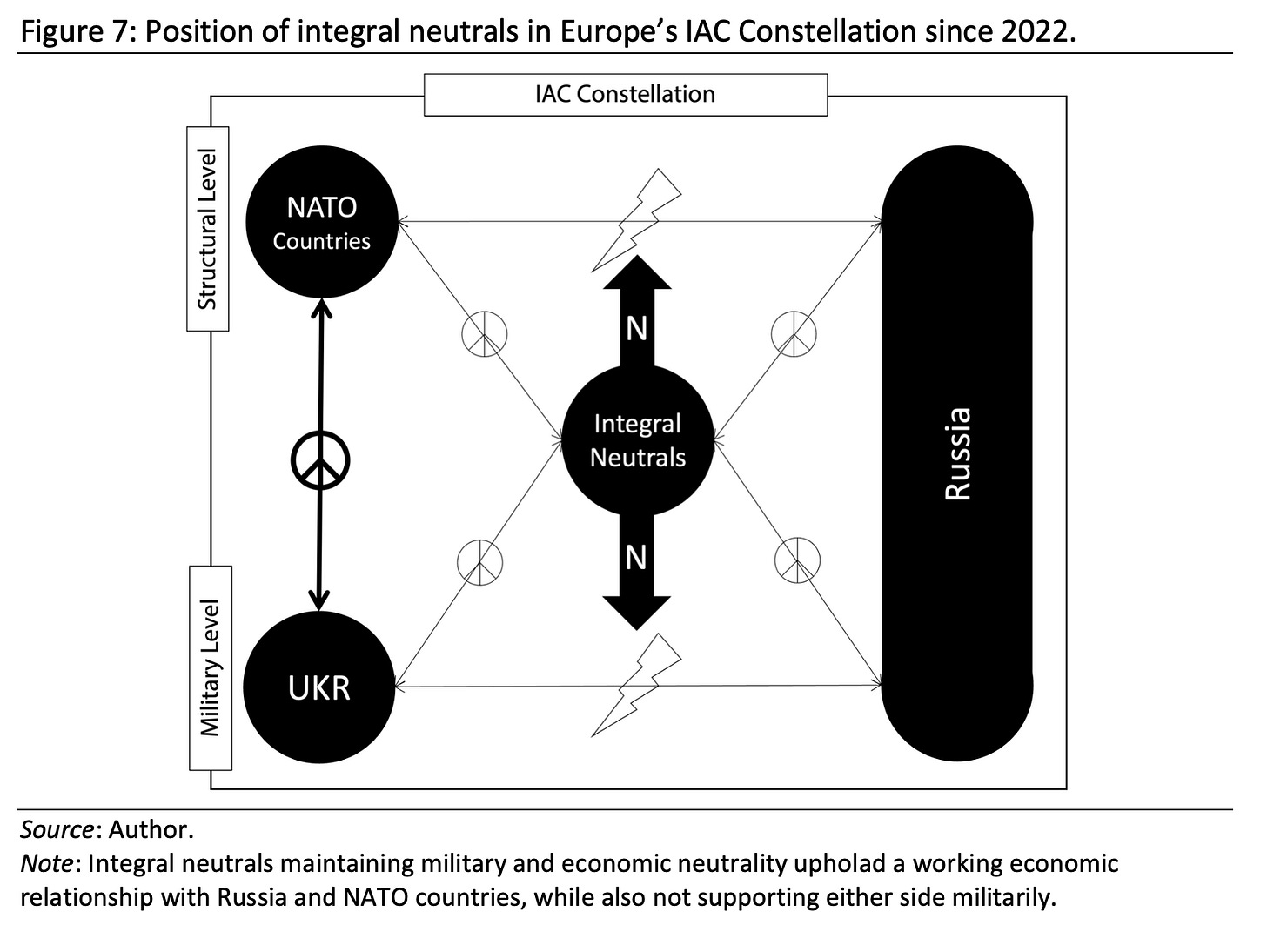

In contrast, many countries around the globe continued their economic relationships with Russia. The list of these states is long, including most of Latin America, Africa, West, East, and Southeast Asia. In addition to not providing weapons to either side of the conflict, they continued trading with Russia just as they did in previous periods, maintaining, in the analytical sense of this paper, an integral neutrality toward the conflict. This position and attitude are represented in Figure 7.

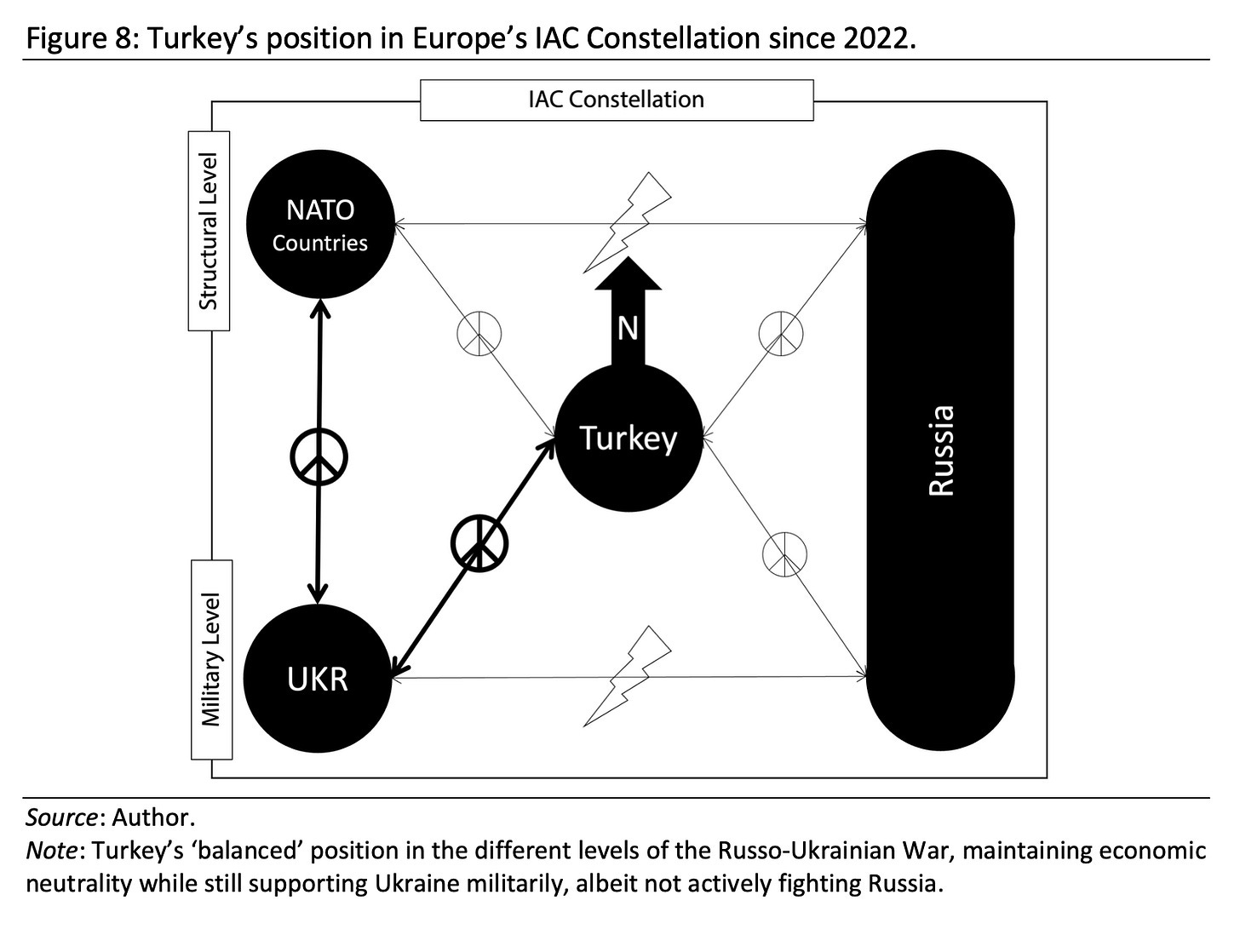

In a slightly different sense, even one NATO state, Turkey, is part of this list of economic neutrals. The difference in the Turkish case is that Ankara in fact supported Ukraine with a limited number of arms, but it refrained from sanctioning Russia.[60] The difference this stance made in terms of Russian perceptions of Turkey is rather striking. Not only did Moscow accept Istanbul as a meeting ground for early peace negotiations in March and April 2022, (before Turkey commenced supplying weapons to Ukraine) but it did so again—even proposing the city by itself—in 2025, leading some analysts to conclude that “Russia and Ukraine chose Türkiye because both have good working relations with Ankara and respect its neutral position.”[61]

In addition to accepting Turkey as a mediator, Russia also refrained from including Turkey on its list of unfriendly countries (a list on which European neutrals like Switzerland, Austria, and Ireland figure prominently), indicating again that Ankara’s stance toward the structural conflict is what to Russia matters more than direct or indirect support of the hot shooting war in Ukraine.[62] This episode exemplifies that when third parties—even those inside military alliances—maintain some form of equidistant policy toward one or the other level of a conflict, the conflict parties might view them as sufficiently friendly to accept them as neutral in the analytical sense of our third-party actor models. In this case, it was Turkey’s dual engagement; the military support to Ukraine on the one hand, while economically continuing interactions with Russia, that struck the balance needed to be deemed trustworthy enough by both sides.[63] Figure 8 depicts this situation.

Depicting Turkey’s economic interactions with all sides of the Ukraine War as a form of (differential) neutrality is not to claim that either Turkey or Russia view these actions as neutral per se, but that the concept can be leveraged usefully in the analytical sense to understand the complex relationship between the different actors. This form of neutrality is neither one according to international law nor a strict policy, and it has nothing to do with moral connotations about warfare. It is a phenomenon emerging from the relationship between the different actors.

Conclusion

Understanding third parties as embedded in conflict constellations and with multitudes of bilateral relations toward all belligerents allows for nuanced conflict analyses. If combined with a differentiation of levels and stages, approaching conflicts from the viewpoint of third-party (neutral) actors adds important information about the multilateral dimension of conflicts. Neutrality in this analytical sense is inescapable because it emerges logically as a relational property when third parties take note of a conflict. Unless an actor is completely removed from a conflict to the point where they lack all and any knowledge about it (the man in the moon), all decisions taken in regard to it create a larger conflict constellation that the third party must deal with in one way or another.

The fact that third-party actors take varied approaches toward the different levels of conflicts then creates complex interaction situations. Those might seem odd when viewed from belligerent or alliance perspectives, but they are well understandable when viewed strictly from the position of the third party. As we have seen with the example of the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact and Turkey’s role in the Russo-Ukrainian-NATO conflict constellations, even neutrality in alliance systems or belligerent neutrality are not contradictions in terms, but a natural outcome of possible multilateral conflict constellations. While this understanding of neutrality might be at odds with an absolute understanding of neutrality as a policy of permanently neutral states, it is, in fact, congruent with definitions of occasional neutrality under international law and historically a well-established practice of states.

While these models cannot tell us who will or will not be a neutral third party—and in what sense they will remain neutral—they do help us understand the complexity of neutral-belligerent interactions and the possible choices neutral actors have. These models are not to be taken as a complete taxonomy or finished theoretical framework, but it is hoped that they will help the development of a comprehensive, sociological theory on third-party actors in various conflict constellations. More formalization will be needed to move toward a deeper understanding of patterns across conflict constellations and their various levels.

References

– Omitted in Pre-Print Version —

[1] See, for instance, Malmborg Ma (2001) Neutrality and State-building in Sweden. New York: Palgrave, Jorio M (2023) Die Schweiz und ihre Neutralität. Zurich: Hier und Jetzt.

[2] See, for instance, Ørvik N (1953) The Decline of Neutrality 1914-1941. With Special Reference to the United States and the Northern Neutrals. Oslo: Johan Grundt Tanum Forlag, Neff SC (2000) The Rights and Duties of Neutrals: A General History. Manchester: Manchester University Press, Abbenhuis MM (2014) An Age of Neutrals: Great Power Politics, 1815-1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[3] See for instance Oppenheim LFL (1912) International Law: A Treatise—War and Neutrality. London: Longmans, Green, Galiani F (1782) De’ Doveri de’ Principi Neutrali verso i Principi Guerreggianti, e di Questi verso i Neutrali. Naples, Schopfer S (1894) Le Principe Juridique de la Neutralité et son Évolution dans l’Histoire du Droit de la Guerre. Lausanne: Corbaz, Tswettcoff D (1895) De la situation juridique des États neutralisés en temps de paix. Geneva: Kündig, Kleen R (1898-1900) Lois et Usages de la Neutralité d’après le Droit International Conventionnel et Coutumier des Etats Civilisés. Paris: A. Chevalier-Marescq, Winslow E (1907) Neutralization. The North American Review 186(622): 83–90, Bustamante ASd (1908) The Hague Convention Concerning the Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers and Persons in Land Warfare. The American Journal of International Law 2: 95-120, Winslow E (1908) Neutralization. American Journal of International Law 2: 366–386, Wicker CF (1911) Some Effects of Neutralization. The American Journal of International Law 5(3): 639-652, Kennedy C (1913) Neutralization and Equal Terms. Ibid. 7(1): 27-50.

[4] Thucydides (431 BC) The History of the Peloponnesian War. London: Longmans.

[5] Kautilya (300 BCE (1915)) Arthashastra. Bangalore: Government Press.

[6] On Thucydides and ancient Greek notions of neutrality, see also Bauslaugh RA (1991) The Concept of Neutrality in Classical Greece. Berkeley: University of California Press.. On Kautilya, see Sastry KKR (1954) A Note on Udasina: Neutrality in Ancient India. Indian Yearbook of International Affairs 3: 131–134.

[7] Agius C and Devine K (2011) Neutrality: A Really Dead Concept? A reprise. Cooperation and Conflict 46(3): 265-282, Agius C (2006) The Social Construction of Swedish Neutrality: Challenges to Swedish Identity and Sovereignty. Manchester: Manchester University Press, Agius C (2012) Neutrality ‘is what states make of it’: rethinking neutrality through constructivism. The Social Constuction of Swedish Neutrality. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp.32–59, Malmborg Ma (2001) Neutrality and State-building in Sweden. New York: Palgrave.

[8] Cloke K (2001) Mediating Dangerously: The Frontiers of Conflict Resolution. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

[9] For an overview, see Lottaz P (2022) The Politics and Diplomacy of Neutrality. Oxford Bibliographies in International Relations. DOI: 10.1093/OBO/9780199743292-0307.

[10] Plattner D (1996) ICRC Neutrality and Neutrality in Humanitarian Assistance. International Review of the Red Cross 1961-199736(311): 161–180, Forsythe DP and Rieffer-Flanagan BAJ (2007) The International Committee of the Red Cross: A Neutral Humanitarian Actor. London: Routledge.

[11] Kobierecka A and Kobierecki MM (2024) Enforced Ostracism? Analysis of the International Sports Organizations’ Reactions to the 2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine. International Journal of the History of Sport.

[12] Kane A (2022) Neutrality in International Organizations I: The United Nations. In: Lottaz P, Gaertner H and Reginbogin H (eds) Neutral Beyond the Cold: Neutral States and the Post-Cold War International System. Lanham: Lexington Books, pp.91–110, Tay CSE ibid.Neutrality in International Organizations II: ASEAN. In: Lottaz P, Gärtner H and Reginbogin H (eds).

[13] Lottaz P and Reginbogin HR (2019) 'Private Neutrality' – The Bank for International Settlements. In: Lottaz P and Reginbogin H (eds) Notions of Neutralities. Lanham: Lexington, Heath B (2024) Neutrality and Governance in the Weaponized World. American Journal of International Law 118(3): 566–585.

[14] Miskovic N, Fischer-Tiné H and Boskovska N (2014) The Non-Aligned Movement and the Cold War: Belhi – Bandung – Belgrade. London: Routledge, Životić A and Čavoški J (2016) On the Road to Belgrade: Yugoslavia, Third World Neutrals, and the Evolution of Global Non-Alignment, 1954–1961. Journal of Cold War Studies 18: 79-97, Hanhimäki JM (2016) Non-aligned to what? European neutrality and the Cold War. In: Bott S, Hanhimäki JM, Schaufelbuehl JM, et al. (eds) Neutrality and Neutralism in the Global Cold War: between or within the blocs? London: Routledge, pp.17–32.

[15] Brands HW (1989) The Specter of Neutralism: The United State and the Emergence of the Third World, 1947–1960. New York: Columbia University Press, Gabriel JM (2002) Neutrality and Neutralism in Southeast Asia , 1960-1970. The American Conception of Neutrality After 1941. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.119 - 218, Bott S, Hanhimäki JM, Schaufelbuehl JM, et al. (2016) Neutrality and Neutralism in the Global Cold War between or Within the Blocs? New York: Routledge.

[16] Česnakas G and Juozaitis J (2022) European Strategic Autonomy and Small States' Security: In the Shadow of Power. London: Routledge.

[17] Sorensen RA (1992) Thought Experiments. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Tetlock PE and Belkin A (1996) Counterfactual Thourght Experiments in World Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, El Skaf R (2020) Probing Theoretical Statements with Thought Experiments. Synthese 199(3–4): 6119–6147.

[18] Lottaz P (2020) The Logic of Neutrality. In: Reginbogin H and Lottaz P (eds) Permanent Neutrality: A Model for Peace, Security, and Justice. Lanham: Lexington Books.

[19] Ippoliti E (2018) Building Theories: The Heuristic Way. Building Theories: Heuristics and Hypotheses in Science. Cham: Springer.

[20] For a discussion on neutrlaization of states, see Black CE, Falk RA, Knorr K, et al. (1968) Neutralization and World Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[21] Neff SC (2000) The Rights and Duties of Neutrals: A General History. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

[22] Upcher J (2020) Neutrality in Contemporary International Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[23] There is a debate on whether or not the law of neutrality should be regarded as a lex specialis. Compare ibid. and El-Zein J (2023) Das Ende des Neutralitätsrechts. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

[24] Upcher J (2011) Book Reviews: War, Commerce, and International Law. Leiden Journal of International Law 24: 272 - 276.

[25] Morgenthau HJ (1938) The End of Switzerland's Differential Neutrality. The American Journal of International Law 32: 558–562.

[26] Borchard EM and Lage WP (1937) Neutrality for the United States. New Haven: Yale University Press.

[27] Den Hertog J and Kruizinga Sl (2011) Caught in the Middle Neutrals, Neutrality and the First World War. Amsterdam: Aksant.

[28] Gerolymatos A, Smyth D and Horncastle J (2020) Neutral Countries as Clandestine Battlegrounds, 1939–1968: Between Two Fires. Lanham: Lexington Books, Bott S, Hanhimäki JM, Schaufelbuehl JM, et al. (2016) Neutrality and Neutralism in the Global Cold War between or Within the Blocs? New York: Routledge.

[29] Little R (2007) The Balance of Power in International Relations: Metaphors, Myths and Models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Stiles KW (2018) Trust and Hedging in International Relations. Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

[30] See, for example, Hornat J (2023) Hegemonic stability in the Indo-Pacific: US-India relations and induced balancing. International Relations 37(2): 324–247, Korolev A (2016) Systemic Balancing and Regional Hedging: China–Russia Relations. The Chinese Journal of International Politics 9(4): 375–397, Meng W and Hu W (2020) Reacting to China’s rise throughout history: balancing and accommodating in East Asia. International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 20: 119–148.

[31] Howland D (2010) Japanese Neutrality in the Nineteenth Century: International Law and Transcultural Process. Journal of Transcultural Studies 1(1): 14–37.

[32] Oppenheim LFL (1912) International Law: A Treatise—War and Neutrality. London: Longmans, Green.

[33] Neff SC (2000) The Rights and Duties of Neutrals: A General History. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

[34] For a detailed account see Lehmann P (2020) Die Umdeutung der Neutralität: Eine politische Ideengeschichte der Eidgenossenschaft vor und nach 1815. Basel: Schwab Verlag.

[35] Lottaz P, Gaertner H and Reginbogin H (2022) Neutral Beyond the Cold: Neutral States and the Post-Cold War International System. Lanham: Lexington Books.

[36] Slavinsky B (2004) The Japanese-Soviet Neutrality Pact: A Diplomatic History, 1941-1945. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

[37] Lottaz P and Ottosson I (2022) Sweden, Japan, and the Long Second World War 1931–1945. London: Routledge.

[38] Lottaz P (2018) Neutral States and Wartime Japan: The Diplomacy of Sweden, Spain, and Switzerland toward the Empire. National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, Tokyo.

[39] Ito R (2023) A Neoclassical Realist Model of Overconfidence and the Japan-Soviet Neutrality Pact in 1941. Internatioal Relations. DOI: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00471178231218567. 1–24.

[40] Weitsman PA (2010) Wartime Alliances versus Coalition Warfare: How Institutional Structure Matters in the Multilateral Prosecution of Wars. Strategic Studies Quarterly 4(2): 113–138.

[41] The House fo Commons (1866) Treaty of Alliance against Paraguay, signed May 1, 1865, by the Plenipotentiaries of Uruguay, of Brazil, and of the Argentine Republic. Accounts And Papers. London.

[42] The secret protocol to the Non-Aggression Pact did not include an explicit offensive military agreement but implied strongly that future joint military action would be taken and should result in the breaking of Poland, which it ultimately did. For the text in English see Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the USSR (1939) Secret Supplementary Protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Non-Aggression Pact. Wilson Center Digital Archive.

[43] Newnham R (2008) "Coalition of the Bribed and Bullied?" U.S. Economic Linkage and the Iraq War Coalition. International Studies Perspectives 9(2): 183–200.

[44] Kluyver CA (1920) Documents on the League of Nations. Leiden: International Intermediary Institute.

[45] North Atlantic Treaty Organization (1949) The North Atlantic Treaty. Available at: https://www.nato.int/cps/ie/natohq/official_texts_17120.htm.

[46] The Government of the German Reich and The Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (1939) The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Zurich: International Relations and Security Network.

[47] Slavinsky B (2004) The Japanese-Soviet Neutrality Pact: A Diplomatic History, 1941-1945. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

[48] On the mass-violence in the capital Kyiv, see Katchanovski I (2024) The Maidan Massacre in Ukraine: The Mass Killing that Changed the World. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan.. On the dynamics of the conflict see Petro NN (2023) The Tragedy of Ukraine. Boston: De Gruyter.

[49] For a general discussion see the contributions in Hauter J (2021) Civil War? Interstate War? Hybrid War? Dymensions and Interpretations of the Donbas Conflict 2014–2020. Stuttgart: Ibidem., Marples DR (2022) The War in Ukraine’s Donbas: Origins, Contexts, and the Future. Budapest: Central European University Press..

[50] Atland K (2020) Destined for Deadlock? Russia, Ukraine, and the Unfulfilled Minsk Agreements. Post-Soviet Affairs 2(36): 122–139.

[51] Mills C (2022) Military Assistance to Ukraine 2014-2021. House of Commons Library. 1–12.

[52] Preiherman Y and Lottaz P (2022) Belarus: Between Alliance and Neutralism. In: Lottaz P, Gaertner H and Reginbogin H (eds) Neutral Beyond the Cold: Neutral States and the Post-Cold War International System. Lanham: Lexington Books, van der Togt T (2017) Belarus’ Security Concerns: Prospects for a More Neutral Course Between Russia and the West? The “Belarus factor”: From balancing to bridging geopolitical dividing lines in Europe? : Clingendael Institute, pp.14-19.

[53] Bohdan S and Isaev G (2016) Elements of Neutrality in Belarusian Foreign Policy and National Security Policy. Analytical Paper, October 25, Preiherman Y and Lottaz P (2022) Belarus: Between Alliance and Neutralism. In: Lottaz P, Gaertner H and Reginbogin H (eds) Neutral Beyond the Cold: Neutral States and the Post-Cold War International System. Lanham: Lexington Books.

[54] Chupris OI and Smirnova ES (2018) The Neutrality of the Republic of Belarus as Legal Provision. Moscow Journal of International Law 4: 107-115, Melyantsou D (2019) Situational Neutrality: A Conceptualization Attempt. Minsk Dialogue.

[55] TASS (2022) Russian Government Approves List of Unfriendly Countries and Territories. TASS-Russian News Agency.

[56] Swiss Info (2022) Russia Rejects Protecting Power Mandate Agreed by Switzerland and Ukraine. Available at: https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/politics/switzerland-and-ukraine-agree-draft-protecting-power-mandate/47817660.

[57] Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (2022) Questions and Answers on Switzerland's Neutrality. February 28.

[58] Ministroy of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation (2024b) Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s remarks at the 13th Middle East Conference of the Valdai Club, Moscow. February 13.

[59] Ministroy of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation (2024a) Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s answer to a question during his remarks at the Committee on Foreign Affairs of the Federation Council of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation. Press Service, May 13.

[60] Dost P (2024) The Ukraine-Turkey defense partnership with the potential to transform Black Sea and Euro-Atlantic security. Atlantic Council.

[61] Teslova e, Eruygur B and Aktas A (2025) Istanbul talks: Why Russia and Ukraine view Türkiye as a reliable mediator. Anadolu Agency, May 14.

[62] Government of the Russian Federation (2024) Распоряжение Правительства Российской Федерации от 17.09.2024 № 2560-р. Moscow: Offuce of Official Publication of Legal Acts.

[63] Gürer C and Walczak E (2024) Russian-Turkish Strategic Cooperation in the New Security Environment. Small Wars Journal.

Pascal, the peace symbol should be turned upside down. You can check it on the peace Nobel prize website about Gerald holthom 's interview. Or you can Read Billy Meier' s material.

Nice intervention.